During World War 2, the US Air Force had a problem.

Planes were returning to base riddled with bullet holes, so the military decided it needed better ways to protect the planes and the crew.

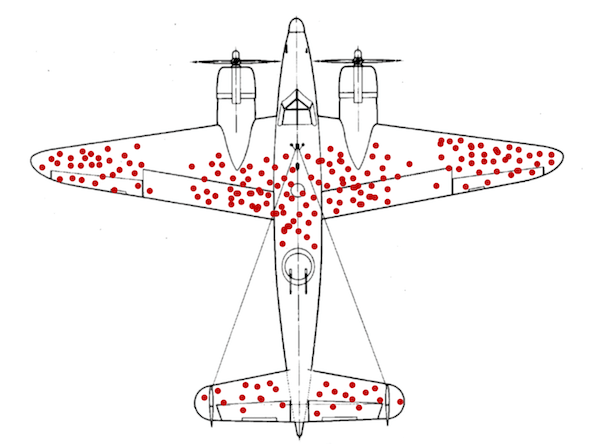

When they plotted out the damage the planes were incurring, it was concentrated around the tail, body, and wings. So the USAF immediately set forth to reinforce these areas.

That is until Abraham Wald, a statistician and mathematician, made a key observation — they were only looking at the damage on RETURNING planes. They hadn’t factored in damage inflicted on planes that FAILED to return.

He proposed bolstering the armor where there were no dots at all, like around the engines. As unlike the tail, body, and wings, the engines were extremely vulnerable. Planes hit there never made it back to base to have their damage charted out.

From Wikipedia: The damaged portions of returning planes show locations where they can sustain damage and still return home; those hit in other places do not survive. (Image shows hypothetical data.)

Photo: McGeddon

This story — not my original work; see here and here — is an example of Survivorship Bias, a form of cognitive bias that occurs when decisions are made based on past successes while ignoring past failures.

Survivorship Bias in Fitness

According to Anders Noren, its also pervasive in the fitness industry with coaches using successes (such as dramatic 12-week transformations) as proof their training advice is solid while never questioning if a more moderate path would’ve yielded a similar result, or even just more success stories.

“They model their advice around what they see working best for a handful of outliers with little regard to safety, recoverability or sustainability,” says Noren.

In their minds, willpower is the limiting factor, and that any failures rest with the CLIENT, not their training protocol.

Clients with the genetics, motivation, and time to survive the training & diet stick around and get results, adding to the list of the success stories.

As for the rest? They simply flame out, and are replaced with new clients.

“Over time, the trainer sees more and more successes, which they believe are in part a result of their expertise.

“And the successes are now financially supporting the trainer. So those that can train more often and recover faster are the best customers.”

But the failures remain hidden, forgotten, and ignored.

* * *

I’ve written several times that as a coach my client failures weigh me down far more than my successes lift my spirits.

At first, I assumed it was just false modesty on my part, perhaps with a dash of imposter syndrome.

But understanding how the survivorship bias affects coaching helped me understand why I don’t bang the transformation drum more than once or twice a year.

Most fitness advice is adapted from and geared towards the successful, the survivors.

It’s rarely about reducing the failure rate.

Basically we market what CAN be achieved by the few if all the genetic, lifestyle, and motivation stars come into alignment.

So would showing what’s achievable for average folks on a more sustainable “dose” of diet & exercise be more honest?

Perhaps. Though definitely not as compelling an ad.

To me the more important thing is to NOT sweep your failures under the rug and instead put them through a thorough audit:

- Where did the plan go wrong?

- Where did you overshoot?

- At what point did they stop trying?

- Where did you “lose” them?

- What would you do differently?

…and yes, all of the above is ON THE COACH.

Another take on the Survivorship Bias are middle-aged coaches marketing themselves in the over 40 category, seemingly with only “I’m in my forties and I’m in great shape, so listen to me” as their angle.

Now I would NEVER discount the value of first-hand experience, but the holes in logic are enormous.

You’ve spent DECADES building your body while making every honest mistake, and then finally figured out what works, or at least what works for you.

That’s a success story on its own, but it’s N=1.

Its just not the same as someone in their forties who perhaps just started exercising seriously or simply doesn’t want to (or is incapable) make it their top priority.

The biggest thing is, it doesn’t reduce the failure rate.

Why is over 40 (or 50) even a category?

What makes it a different challenge than say a 25 or 35 year old?

I think the middle-aged bracket has unique demands in terms of lifestyle (stress), lack of free time (kids & work), poor sleep, a little existential angst, plus not wanting to give up on youthful vanity while still focusing on bigger targets, like health.

Build a program around the above and now you’re addressing the failure rate.

And once we address our failures, we can finally stop leaving people behind.